Why 400-Year-Old Body Wisdom Still Matters

Renaissance herbalists understood something modern neuroscience and psychoneuroimmunology is finally coming back to—emotions live in the body. The power of our mind and our emotions have so much influence on our health, and the reverse is equally true. While modern medicine is singing the songs of the gut-brain connection and discovering how inflammation drives depression and how trauma lives in tissue, our medical ancestors knew this connection centuries ago and built entire systems of treatment around it.

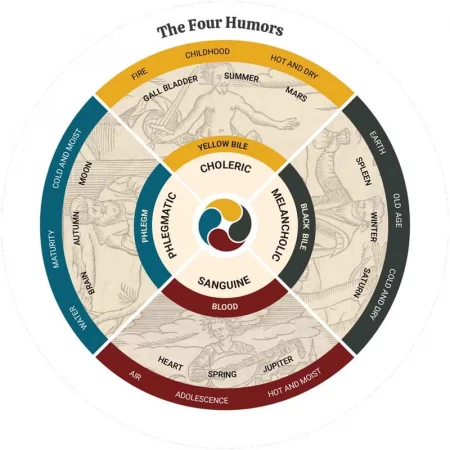

Galen of Pergamon, the second-century physician whose work shaped Western medicine for over a millennium, didn’t just theorize about the four humors—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. As physician to Roman emperors and gladiators, he observed how injury, diet, environment, and emotional states changed the body’s balance of hot, cold, moist, and dry qualities, and how these changes in turn shaped mental and physical health. His humoral framework gave physicians a diagnostic lens for understanding why someone’s depression might need different treatment than another person’s, why some people burned with anger while others froze in fear, and why the treatment had to match the specific imbalance present in that body at that time.

The four temperaments—sanguine, choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic—offer a framework for understanding how our physical state shapes emotional experience. This is material understanding, not metaphor. Galen, later Arabic physicians like Avicenna and Rhazes who expanded on his work, and Renaissance physician-herbalists like Nicholas Culpeper were describing observed physical reality and the mental disturbances that arose from specific bodily conditions. They watched what happened when someone stayed up studying for weeks, when anger persisted for months, when grief turned a person cold and withdrawn. They documented patterns.

The Four Temperaments: What Culpeper Saw

Nicholas Culpeper was a seventeenth-century English physician, herbalist, and astrologer who made medicine accessible to common people by translating medical texts from Latin into English and publishing affordable herbal guides. His 1652 translation of Galen’s work preserves these temperament descriptions with remarkable specificity—not as abstract categories but as recognizable patterns he saw in his patients. We’re using his quotes because he captured the emotional signatures of each temperament with the kind of vivid detail that makes the framework come alive, and because his work bridges ancient Galenic theory with practical herbal treatment that was actually used to help people rebalance their systems.

Sanguine—Hot + Moist

Culpeper described sanguine people as “merry cheerful Creatures, bounteful, pitiful, merciful, courteous, bold, trusty.”¹ But here’s what he really noticed: “a little thing will make them weep, but so soon as ’tis over, no further grief sticks to their Hearts.”¹

High emotional responsiveness with quick recovery. Natural optimism. Social ease. This is what we now call emotional resilience—the capacity to feel deeply and return to baseline. The sanguine temperament moves through emotion like water, quick to tears and quick to laughter, able to metabolize feeling without getting stuck. This is the friend who cries at commercials and ten minutes later is planning the next adventure, the person whose warmth draws others in because there’s no defensiveness blocking connection. The heat gives vitality and movement, the moisture gives flexibility and flow. When balanced, this temperament embodies emotional health—feeling everything, holding nothing, trusting that the next moment will bring something new.

Choleric—Hot + Dry

Culpeper wrote that choleric people were “naturally quick witted, bold, no way shame-faced, furious, hasty, quarrelsom” and “not given to sleep much.”¹ They dreamed “of fighting, quarrelling, fire, and burning.”¹

This is high drive. Quick to anger. Intense focus. The person who can’t stop working and can’t understand why everyone else isn’t moving as fast. The one headed straight toward burnout. The heat gives intensity and speed, but without moisture to cool and soften, it burns. This is the entrepreneur who works sixteen-hour days and feels contempt for people who “waste time” resting, the activist whose righteous anger fuels incredible productivity until the crash comes. The choleric temperament achieves extraordinary things but often at the cost of relationships and health, because the dryness makes them brittle and the heat makes them combative. Sleep becomes impossible because the mind is still strategizing, planning, fighting imaginary battles. Even the dream life becomes work.

Melancholic—Cold + Dry

Culpeper observed that melancholic people had “appetite far better than their concoction”—they wanted more than their bodies could process.¹ Desire exceeded capacity.

The emotional pattern: “naturally Covetous, Self-lovers, Cowards, afraid of their own Shadows, fearful, careful, solitary, lumpish, unsociable, delighting to be alone.”¹ They dreamed “of frightful things, black, darkness, and terrible businesses.”¹

Chronic worry. Perfectionism. Social withdrawal. The overthinker who can’t rest because the mind won’t stop analyzing threat. The cold makes everything feel dangerous and the dryness removes the fluidity needed to adapt, so the melancholic person gets stuck in loops of rumination, always preparing for disaster, always finding evidence that confirms their worst fears. This is the person who lies awake replaying conversations from three years ago, finding proof that everyone secretly hates them, unable to accept comfort because the internal narrative is too fixed, too dry, too cold to be shifted by warmth from outside. The appetite being better than concoction means they hunger for connection, achievement, love, but their system can’t metabolize what it takes in—nothing nourishes because the cold has slowed all processes and the dryness has hardened the capacity to receive.

Phlegmatic—Cold + Moist

Culpeper described phlegmatic people as “very dull, heavy and slothful, like the Scholler that was a great while a learning a Lesson, but when Once he had it—he had quickly forgotten it.”¹ They were “drowsie, sleepy, cowardly forgetful Creatures.”¹

Low energy. Slow processing. Emotional flatness. What we now recognize as the physical depression pattern where moving through the day feels like walking through water. The cold slows everything down and the moisture makes everything heavy, waterlogged, thick. This is the person who needs three alarms to wake up, who can’t remember what they ate for breakfast, who watches life happen from behind a fog they can’t quite penetrate. The phlegmatic state isn’t peaceful—it’s suffocating. There’s too much dampness and not enough heat to burn it off, so everything accumulates. Thoughts move slowly. Emotions feel muted. Decision-making becomes impossible because there’s no fire to drive action forward. Where the melancholic person is hypervigilant and anxious, the phlegmatic person is simply absent, too heavy and cold to engage with threat or opportunity.

The Burning Question: Adust Choler and Modern Burnout

Here’s where Renaissance medicine documented something neuroscience is only now measuring. The concept of adust choler—when hot, dry anger burns itself out and becomes cold, dry melancholy.

Elena Carrera’s research into sixteenth and seventeenth-century Spanish medicine reveals this wasn’t poetic metaphor. Medical texts “related them to actual bodily fluids, vapours and fumes, which could be observed (or smelt) in bodily secretions and emissions (like faeces, vomit or eructations).”² These physicians watched anger transform into depression through observable physical changes.

The medical understanding was precise: “a cold and dry mixture of humours would make people fearful. By contrast, those with a hot and dry temperament (whether innate or acquired), would be prone to anger, and their imagination would be more easily deranged.”² And here’s the intervention point: “Their anger and their derangement could be reduced if they ate fattier foods, or slept and rested for longer.”²

This is the burnout pattern we see everywhere now. But it’s not just the choleric-to-melancholic crash that demonstrates how temperaments shift under stress—each humor can burn out in its own way. The sanguine person who stays optimistic and social through crisis after crisis eventually loses their heat and moisture through constant emotional output, becoming cold and flat, unable to access the joy that once came naturally. The melancholic person who runs on anxiety and hypervigilance can heat up their cold, dry state into hot, dry mania—the kind of wired, sleepless, paranoid state where the fear becomes frantic action. The phlegmatic person who’s been cold and damp for months might add heat without adding dryness and shift into hot, moist fever states—inflammation, autoimmune flares, infections that won’t resolve. Every temperament has a breaking point where the qualities intensify or invert under sustained pressure.

But that choleric-to-melancholic crash remains the most common burnout pattern in our culture that glorifies productivity and demonizes rest. High achiever running hot and dry (choleric). Pushing through exhaustion. Then the crash into cold and dry (melancholic)—can’t get out of bed, can’t focus, can’t care. The heat has burned itself out and taken all the moisture with it, leaving someone brittle, frozen, afraid of everything. This is what adust choler describes: choler (yellow bile, hot and dry) that has been burned or overheated (adustus) until it transforms into melancholy (black bile, cold and dry). The angry ambitious driven person becomes the depressed withdrawn fearful person, and to the Renaissance physician, this was a predictable physical transformation with a specific treatment protocol.

From Theory to Treatment: The Six Non-Naturals

Renaissance physicians identified specific factors that shifted bodily temperature and moisture—what they called the “non-naturals” because they weren’t fixed at birth.² These were the variables you could change to prevent or treat mental disturbance.

The six non-naturals: Air. Food and drink. Sleep and waking. Movement and rest. Retention and elimination. Passions of mind.

Medical texts emphasized that “mental disturbances were caused by a wide range of factors, including diet, climate, the quality of the air breathed, and daily routines such as exercise, physical and mental exertion, rest and sleep.”² Change these factors and you change the mixture of bodily qualities—heat, cold, moisture, dryness—which influenced “not only physical health, but also the functioning of the brain and the emotions.”²

These are the same properties we focus on today in wholistic medicine—the lifestyle factors that functional medicine practitioners assess, the nervous system inputs that trauma therapists work with, the circadian rhythm disruptions that sleep researchers document, the inflammatory triggers that integrative doctors investigate. We’ve renamed them and we measure them differently, but we’re still asking the same questions: What are you eating? How are you sleeping? Are you moving your body? Are you breathing clean air? Are you eliminating properly? What emotional patterns are you holding? The six non-naturals map almost perfectly onto modern integrative health assessments because these factors genuinely do shape health and disease, mood and cognition, resilience and breakdown.

This is precision medicine, Renaissance style. Dietary advice occupied “a prominent position in handbooks on the preservation of health” because food directly altered temperament.² The Hippocratic principle: contraria contrariis curantur—opposites cure opposites.²

Running too hot? Eat cooling foods like lettuce, cucumber, watermelon. Running too cold? Warming broths with ginger and garlic, spices that kindle heat. Too dry from constant mental work? Fatty foods and moisture—olive oil, avocados, rich bone broths. Too damp and heavy? Drying herbs like thyme and rosemary, foods that clear phlegm. The treatment matched the imbalance, and the physician’s skill was in reading the specific pattern present in that person at that time and adjusting treatment as the pattern shifted.

Your Temperament Is Not Your Destiny

Here’s what gets lost when people treat the four temperaments as personality types to identify with. Carrera’s research makes this clear: “Even though people were believed to be born with a given complexion or temperament (or combination of bodily qualities), this would change with age, and depending on their environment and lifestyle.”²

Culpeper described temperaments but he also described treatments. These are dynamic states that shift based on how we live, what we eat, how we sleep, where we direct our mental energy. The framework offers diagnostic precision—are you burning hot right now, irritable and driven and restless, unable to sleep? Or running cold, withdrawn and exhausted, unable to engage? The answer tells you what your body needs, and the answer changes depending on what season you’re in, what stress you’re under, what resources you have access to.

Medieval and Renaissance medical texts made “a clear distinction between people’s innate temperament (or complexion) and their actual bodily and moral disposition, based on their temporary (and always changing) mixture of humours.”² You weren’t trapped in one state. The mixture was always in motion. Someone born with a melancholic temperament might spend most of their life in fairly balanced states, only dropping into cold, dry depression during periods of grief or isolation or overwork. Someone born sanguine might develop choleric heat during their ambitious thirties, then shift into phlegmatic dampness in their sixties if they stop moving and become sedentary.

This matters for understanding burnout, because the driven person (choleric heat) who crashes into depression (melancholic cold) hasn’t changed personality types or developed a chemical imbalance that requires lifelong medication. They’ve depleted their heat and moisture through overwork, through chronic stress, through the sustained output of energy without adequate input of rest and nourishment. The body shifted from one state to another based on how it was used, and the body can shift back when the inputs change.

The treatment follows the diagnosis. Choleric burnout needs cooling, moistening, resting—literally lying down in cool dark rooms, eating fats and drinking water, doing nothing for long enough that the heat can dissipate and moisture can return. Melancholic withdrawal needs gentle warming, movement, social connection—small amounts of stimulation that don’t overwhelm, herbs that kindle warmth without burning, practices that soften the dryness and coax the system back into motion. Phlegmatic stagnation needs stimulation and heat—vigorous movement, spicy foods, activities that demand engagement, anything that burns off the accumulated dampness and gets energy circulating again. Sanguine overwhelm needs grounding and drying—structure, routine, practices that contain all that flowing energy so it doesn’t just dissipate, herbs that consolidate and focus rather than expand and excite.

Embodied Emotions, Then and Now

The thing that draws me back to these old texts the most is that Renaissance physicians didn’t separate mind and body. Through over a decade of practicing medicine and three-plus decades of living life as an emotional human, I know this to be true as well. With mind-body medicine and psychoneuroimmunology, modern medicine is getting the hint. The physicians working in the Galenic tradition spent their whole careers watching the interaction of mind, body, and spirit—how cold makes people fearful, how anger heats the body, how sadness thickens and darkens the blood, how excessive study consumes heat and leaves the body cold and dry.²

Modern research validates this material basis through different language. We measure cortisol curves instead of hot and dry humors. We study the gut-brain axis instead of retention and elimination. We document HPA axis dysfunction instead of adust choler. But we’re describing the same phenomenon: mental states emerge from and affect physical states in observable, measurable, treatable ways. The research on trauma and the nervous system confirms what Renaissance physicians knew—that fear lives in the body as cold and contraction, that rage lives as heat and tension, that grief drains warmth and vitality, that joy increases circulation and warmth.

The question when emotions arise becomes physical: Am I running hot or cold right now? Moist or dry? The body knows before the mind does, and the body speaks through signals we’ve been taught to ignore—skin temperature, digestive capacity, sleep quality, energy levels, emotional reactivity. These aren’t separate systems sending separate messages. They’re one interconnected pattern expressing itself through multiple channels, and when we learn to read the pattern, we can work with it instead of against it.

Notice the physical state when emotions arise, and you’ll start to see the temperaments in motion—the way anxiety makes you cold and dry, the way anger heats you up, the way sadness weighs you down with dampness, the way joy makes everything feel warm and fluid. Treat the body to support the mind by choosing foods and herbs and activities that rebalance the qualities that have become excessive or deficient. This is what Renaissance herbalists knew and what Culpeper documented in 1652 with such precise attention to pattern and detail. The four temperaments aren’t categories to identify with or personality types to defend. They’re states to recognize, understand, and gently shift through the non-natural factors we control—air, food, sleep, movement, elimination, and how we meet the passions of mind that shape our days and our lives.

Sources

- Culpeper, Nicholas. Galen’s Art of Physick. Translated by Nicholas Culpeper. London, 1652. pp. 52-57.

- Carrera, Elena. “Understanding Mental Disturbance in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Spain: Medical Approaches.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 87, no. 8 (2010): 105-136.

- Sullivan, Erin. Beyond Melancholy: Sadness and Selfhood in Renaissance England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Note: This exploration of historical temperament theory is offered for educational purposes and to honor the lineage of emotional herbalism. It does not replace modern medical care or mental health treatment. The historical framework can complement but not substitute contemporary therapeutic approaches.