Melancholy—these days it means wistful sadness, maybe a moody afternoon, something fleeting. But in historical medical texts, melancholy meant so much more.

It was a particular kind of heaviness that medieval and Renaissance physicians understood as a physical disease with profound effects on mind and spirit. Melancholy wasn’t just a feeling—it was a measurable imbalance in the body’s humours with cascading physical and mental consequences.

The Framework: Four Humours and Melancholy’s Place

For over a thousand years—from Galen in the 2nd century through Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine (980-1037 CE) to Robert Burton’s monumental Anatomy of Melancholy (1621)—physicians mapped melancholy as an excess of cold, dry black bile affecting the entire system.1

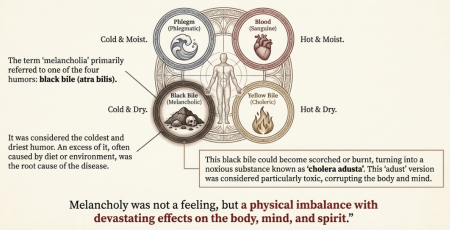

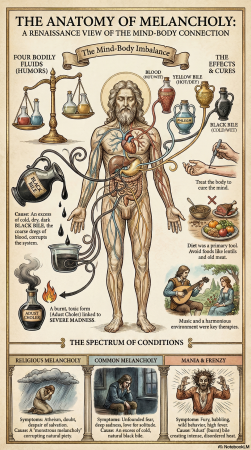

The Galenic framework taught that health depended on balance among four humours: blood (sanguine: hot and moist), yellow bile (choleric: hot and dry), phlegm (phlegmatic: cold and moist), and black bile (melancholic: cold and dry). Each humour corresponded to a temperament, and when any humor became excessive, disease resulted. Melancholy was the coldest and driest state possible—and when this bile became scorched or burnt, it transformed into something far more dangerous.

Spanish physician Andrés Velásquez, in his Libro de la melancholia (1585)—believed to be the earliest treatise on melancholy written in a European vernacular language—explained that physicians distinguished between natural black bile and what he called atra bilis: the noxious burnt or putrefied bile that turned toxic and corrupted both body and mind.2 This wasn’t metaphor. Velásquez described melancholic humour based on clinical observation: “black, thick, earthly and pungent,” noting it was caustic enough to cause death in some forms of dysentery.3

This framework meant melancholy wasn’t just one thing. It existed on a spectrum—from temperament (the scholar’s natural constitution) to disease (prolonged suffering requiring treatment) to mania (when burnt bile created visions and terror). It was a matter of degree, of how deeply the cold, dry state had taken hold.

What Melancholy Feels Like: Recognizing the Pattern

Maybe you recognize this: sadness that settles into your chest and won’t lift. Not the acute grief of loss, but something slower, colder. A gradual withdrawal where even things that used to bring joy feel distant and grey. Your body feels heavy—like moving through cold water. Thoughts turn circular, dwelling on what’s wrong, what’s missing, what might go wrong next.

The old physicians would say your constitution is becoming cold and dry. Modern signs they would have recognized: waking at 3am with anxious thoughts, digestive issues that won’t resolve, chronic tension in shoulders and jaw, a persistent sense that something is wrong even when externally things are fine. Your appetite changes—craving heavy, dense foods or losing interest altogether. Social connection feels like too much effort. The world narrows.

This is how melancholy grows. It starts small—a few nights of poor sleep, increased stress, digestive upset. The cold, dry state feeds on itself. Poor digestion creates more stagnation. Stagnation creates more heaviness. Heaviness creates more isolation. Renaissance physicians documented this progression carefully: Santa Cruz noted that typical early symptoms included “unfounded fear, sadness, or hatred for one’s relatives, the desire for solitude and darkness, unjustified anger and visions.”3 The cycle deepens until what started as a tendency becomes a condition requiring intervention.

The Three Types: Where Melancholy Originates

Physicians categorized melancholy based on its physical origins, knowledge that parallels what modern medicine is rediscovering about body-mind connections.

Idiopathic melancholy originated in the head when brain blood burned from excessive heat, causing sleeplessness, headaches, and dark visions. Modern research on neuroinflammation and mood disorders maps remarkably onto this Renaissance understanding of “brain blood burned by excessive heat.”

Hypochondriacal melancholy rose from vapours in the stomach, spleen, or liver—bringing flatulence, acidic vomit, and weakness that spread upward into emotional states. This directly parallels current research on the gut-brain axis, demonstrating how digestive inflammation affects mood and cognition through the vagus nerve and inflammatory markers.4

Sympathetic melancholy affected the whole body’s blood when burnt melancholic humour was produced systemically, bringing prolonged sorrow and terror. This connects to modern understanding of how systemic inflammatory markers in the bloodstream—cytokines, C-reactive protein—affect mental health and emotional regulation.5

Avicenna’s systematic approach in the Canon required identifying the type before treatment: address the physical root, clear what needs clearing, warm what’s become cold, moisten what’s become dry. This wasn’t theory—it was centuries of clinical observation about what actually worked when bodies moved through melancholic states and what helped them return to balance.

When Bodies Shape Souls and Societies

Two Renaissance thinkers pushed the implications of humoral melancholy into profound territory—one spiritual, one societal.

Marsilio Ficino in his Three Books on Life (1489) believed atheism itself was a symptom of a body dominated by cold, dry black bile. Disbelief was a medical condition. His work presented as a practical health guide for melancholic scholars—prescribing solar remedies like saffron steeped in wine, pleasant scents, music that moves through the body. But his deeper purpose was theological. He called his remedies esca—bait. Lure melancholic doubters with help for their bodies and you might heal their souls, opening their minds back to faith. If melancholy could corrupt faith itself, treating the body became essential to spiritual health.

Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) made an even more radical leap: he applied the medical framework of melancholy to entire societies. “Kingdoms, provinces, and political bodies are likewise subject to this disease,” he wrote. “The world itself suffers from a melancholy state.” Divines lost in “reedless speculations,” statesmen ruled by “malice, envy, factiousness, and selfish greed,” lawyers motivated by greed, preferring their own good to the common good.6

The sickness is not just in us—it is in our institutions.

This feels strikingly contemporary. We still diagnose collective dysfunction using the language of individual pathology—toxic workplaces, sick systems, societal depression. Burton’s insight that melancholy operates at every scale from individual body to body politic remains uncomfortably relevant. When institutions are structured around extraction and competition rather than nourishment and cooperation, when systems reward cold calculation over warm connection, we’re still dealing with the same cold, dry imbalance the Renaissance physicians mapped. Just with different language.

What the Old Healers Knew

The Renaissance physicians understood something modern medicine is still learning—the divide between physical and emotional is mostly artificial. Melancholy showed them this clearly. Cold, dry black bile didn’t just cause digestive issues or headaches. It caused prolonged sorrow, terror, loss of hope. Physical symptoms and emotional states were inseparable because they arose from the same source—the body’s humoral imbalance.

When they prescribed warming, moistening herbal remedies, they were addressing the root cold, dry state that manifested as both physical weakness and emotional heaviness. Remedies that brought warmth didn’t just affect the body—they addressed the literal coldness that made the heart feel closed.

They mapped the physical origins in different body systems. They created specialized hospitals across Europe, demonstrating widespread medical commitment to treating these conditions systematically. They knew intellectuals were especially vulnerable—intense study “dries out the brain,” exacerbating the melancholic state. That the deepest thinkers carried this weight because they saw clearly what others missed. And they knew melancholy required both systematic medical treatment and philosophical companioning.

Gentle Support for Cold, Dry States

If you recognize yourself in these patterns—the heaviness, the cold withdrawal, the cycle that feeds on itself—the Renaissance physicians would encourage gentle warming and moistening.

Simple practices: warm baths, warm drinks, foods that bring moisture and gentle heat. Movement that generates warmth without depleting—walking in sunshine, gentle stretching, anything that gets you out of the cold, contracted state. Music and pleasant scents—these aren’t luxuries but medicines that counter the sensory withdrawal of melancholy. Connection with others even when it feels like too much effort. Being in spaces that feel warm and nourishing rather than cold and isolating.

But here’s what the old physicians knew that matters most: melancholy at a certain depth requires help. The person experiencing it cannot always see their way out alone because the condition itself distorts perception. As Santa Cruz warned, physicians had a professional duty to detect and treat melancholic disease early, “evacuating the melancholic humour to prevent it from evolving” into something more severe.3

If the heaviness has deepened beyond temperament into disease seeking out a healer who understands how to work with the whole system is important. A skilled herbalist, naturopathic doctor, or physician trained in constitutional medicine can help identify your specific pattern and address the physical roots. They can prescribe warming, moistening herbs tailored to whether your melancholy originates in the head, the gut, or systemic inflammation. They can help break the cycle before it deepens further.

The humoral framework might sound archaic, but what it describes—constitutional patterns, systemic imbalances, the way physical and emotional states interweave—remains profoundly relevant. Finding someone who can see you clearly, map where the cold and dry has taken hold, and guide you back toward warmth and moisture and balance. That ancient wisdom of seeking help rather than trying to manage alone—it still holds.

Reconnecting with Ancient Wisdom

These historical conditions are not distant curiosities. Burton’s diagnosis of collective melancholy—societies structured around extraction rather than nourishment, institutions rewarding cold calculation over warm connection—describes our present moment with uncomfortable precision. When work systems demand constant productivity while stripping away rest, when economic structures require competition over cooperation, when social media creates connection without warmth, we are living in the cold, dry state the Renaissance physicians mapped. The melancholy isn’t just in individual bodies anymore. It’s embedded in how we’ve organized our collective life.

What the old physicians understood—and what we’re slowly remembering—is that you cannot separate individual healing from the conditions that created the illness in the first place. Yes, seek the herbalist who can address your specific constitutional pattern. Yes, find the practitioner who sees the whole picture and can guide you back toward warmth and balance. But also recognize that your heaviness isn’t personal failure. It’s a reasonable response to systems designed to extract rather than sustain, to deplete rather than nourish. The melancholic state Burton described in institutions hasn’t gone anywhere. We’ve just stopped calling it by name.

But here’s what reconnecting with this history offers: you are not the first person to feel this way. Your ancestors—across centuries, across cultures—knew this heaviness. They named it, mapped it, and found ways to move through it together. When we reach back to these older understandings, we’re not just learning archaic medicine. We’re remembering that healing has always required community, that our bodies and emotions were never meant to be separated, that the plants and practices and patterns of care are still here because they work. This continuity matters. It reminds us that even in our most isolated moments, we’re part of an unbroken lineage of people who felt deeply, suffered meaningfully, and found their way back to warmth. The path forward isn’t about returning to some imagined past—it’s about reclaiming the wisdom that got left behind when we started treating bodies as machines and emotions as inefficiencies. The plants are still here. The patterns are still here. And the understanding that healing requires treating body and soul and society together—that ancient knowing is rising again, calling us back to what we’ve always needed: connection, warmth, witness, and the courage to see clearly what’s making us sick.

References

-

Klibansky, Raymond, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl. Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art. New York: Basic Books, 1964.

-

Velásquez, Andrés. Libro de la melancholia (Sevilla: Hernando Díaz, 1585). In El siglo de oro de la melancolía: textos españoles sobre las enfermedades del alma, ed. Roger Bartra, 255-372. México, D.F.: Universidad Iberoamericana, 1998, pp. 322-29.

-

Carrera, Elena. “Understanding Mental Disturbance in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Spain: Medical Approaches.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies LXXXVII (2010): 105-136.

-

Mayer, Emeran A., Rob Knight, Sarkis K. Mazmanian, John F. Cryan, and Kirsten Tillisch. “Gut microbes and the brain: paradigm shift in neuroscience.” Journal of Neuroscience 34, no. 46 (2014): 15490-15496.

-

Miller, Andrew H., and Charles L. Raison. “The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target.” Nature Reviews Immunology 16, no. 1 (2016): 22-34.

-

Ficino, Marsilio. Three Books on Life (1489). Trans. Carol V. Kaske and John R. Clark. Tempe, AZ: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1989.

-

Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Oxford: Henry Cripps, 1621. Modern edition: eds. Thomas C. Faulkner, Nicolas K. Kiessling, and Rhonda L. Blair. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989-2000.